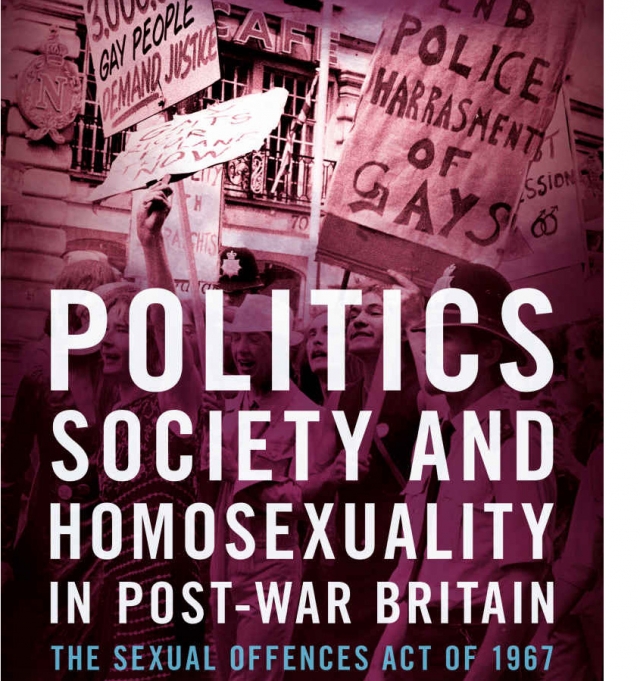

Politics, Society and Homosexuality in Post-War Britain

Book review

The Sexual Offences Act of 1967 and its significance

Politics, Society and Homosexuality in Post-War Britain: the Sexual Offences Act of 1967 and its significance

Keith Dockray Fonthill Media, 2017, 96 pp., £14.99. ISBN 978-1-78155-624-5

This book is a good introduction to the legislation concerning and the Establishment attitudes towards gay or ‘homosexual’ society from the latter half of the nineteenth century through to the start of the twenty-first. Although the author points out that it was in fact Henry VIII who introduced the first law in 1533 concerning ‘sodomy’ it was not until the nineteenth century that attitudes hardened and legal actions started to be taken against men for same-sex relations.

This book is not a history of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) movement as its focus is on the legislation and the politics and victims of the legislation. That legislation was overwhelmingly directed at same-sex relations between men; same-sex relations between women were not even considered by the law. That in part is a reflection of the general attitude to women as a whole during that period, who along with children were to be protected but were rarely viewed as equal. It is also true that women who displayed a desire for other women could still be forced into traditional sexual relations with men whether they were willing or not. Further, anyone who considered themselves as bi-sexual would simply have presented themselves as heterosexual to avoid any conflict with Victorian conservatism.

One of the striking features of the book is the recording of the language and attitudes towards (the newly-defined) ‘homosexual’ men in the nineteenth century through to the changes in the law in the 1960s. The language is blatantly prejudicial, negative and openly offensive to those of us who grew up in the post-1967 era. The vehemence in the language coupled with the penalties enforced by the Establishment provide evidence enough as to why many men chose to hide their sexuality and for many decades did nothing to campaign against the law. In fact that is one of the themes that emerges, that the problem of campaigning against the law was difficult for the gay community unless a man was happy to open himself up to prosecution. It took, therefore, politicians and other Establishment figures to argue that the law was backward and archaic in a modern society and needed changing. The Wolfenden Report of 1957 was the first sign that some members of the British Establishment were beginning to soften in their attitudes towards ‘gay men’ although its recommendations would take another decade to start to be put into practice. Notably once the law was changed in 1967, it allowed the gay community to provide its own leaders and campaigners.

What the author does well is present some of the cases of those who were famously convicted for their behaviour as well as reporting on some of the lesser known or now forgotten cases such as the trial of Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, Michael Pitt-Rivers and Peter Wildeblood. Providing some of the wider social context for why the legislation and attitudes were upheld in law and across society is also a strength of the book. It is sometimes easy to forget that attitudes against many groups were deeply prejudicial for a long time and that Britain was still a country that made moralising judgement on people based on class and background. At Peter Wildeblood’s trial in 1954, the prosecuting counsel stressed the ‘social gulf’ between Wildeblood and the man who he was accused of being involved with and of that being part of the ‘perversion’. Wildeblood retorted:

"Nobody ever flung at me during the war that I was associating with people who were infinitely my social inferiors."

Unfortunately the authors do not place the struggle of gay men in the context of the wider civil struggle for equality and women’s rights.

What we are reminded of by the book is that 1967 ended the law against ‘homosexual’ men but did not bring equality to them or other members of the LGBT community – it would take another 40 years to achieve that. And if I can put that into a wider context – those achievements are in the UK and a handful of other countries, and there are many countries where the language of the nineteenth century is still used, and the ideas it represents believed. When directed at the LGBT community the outcomes are often tragic.