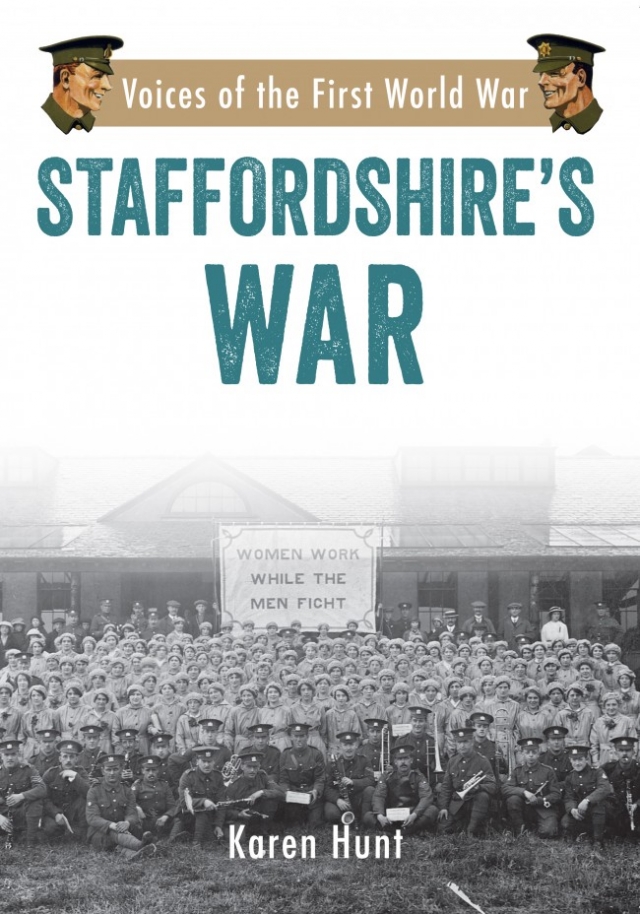

Staffordshire’s War: Voices of the First World War

Book review

Staffordshire’s War: Voices of the First World War, Karen Hunt, Amberley, 2017, 160p, £14-99. ISBN 978-1-4456-5785-1

In Staffordshire’s War Professor Karen Hunt has reflected the best intentions of the Editors of The Historian when they initiated their ‘Aspects of War’ series of articles, designed to explore the widest possible context and effects of the First World War during the four year-long centenary commemorations of that conflict.

Karen Hunt has explored a vast range of ways in which Staffordshire was affected by this international conflict, without being drawn into the details of the conflict itself, just as the ‘Aspects of War’ series has tried to do. However, the extra dimension to this research, additionally, entitled Voices of the First World War, is our introduction to the papers of the Mid-Staffordshire Military Service Appeal Tribunal.

Properly speaking these archives, stored in the Staffordshire Record Office, should not exist. After the Great War, very clear guidance was issued nationally that the papers of military appeals tribunals, with two exceptions (of which Staffordshire was not one) should be destroyed. The reasoning was that certainly public scrutiny of the sensitive decisions made by the tribunal could have potentially explosive effects immediately after such a devastating conflict, with a great deal of private commercial information relating to individuals who had sought exemption. The instruction to destroy these materials was disregarded by Eustace Joy, who was the Clerk to the Staffordshire County Council from 1907 until 1933 and who served as one of the advisers to these military tribunals. He retained all the bureaucratic material – completed forms and supporting correspondence – for every case heard by Staffordshire’s Appeal Tribunal, with these materials being deposited with his personal papers in the Staffordshire Record Office after his death in 1940.

In 2014 Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archive Service were awarded a Heritage Lottery Fund grant to open up the Tribunal’s papers for public scrutiny, and a team of volunteers were recruited to catalogue and process what was available. The fruits of this activity are well reflected in Karen Hunt’s book.One feature of the work of the Tribunal was in their dealings with conscientious objectors. There were different groups: some just did not wish to fight but accepted that they would have to play their part in the war effort; some had much stronger feelings; and for some there were religious dimensions to how they responded. Chapter 7 has some interesting insights into what happened. For example the Christadelphians were a particular religious perspective which caused some difficulty: there was a blend of suspicion of a Christian group which had its origins abroad intermixed with extra factors, such their refusal to undress for medical examinations at Whittington Barracks on religious grounds. There is some evidence that some Christadelphian businessmen faced much higher fines when found to have broken food regulations, without this having been overtly stated. The more one explores the more complex the situation: one man appealed for exemption on religious grounds from enlisting and his exemption was allowed, and he then continued his work at a factory in Birmingham where he was working on an assembly-line, manufacturing hand grenades, the inherent conceptual contradiction of this situation being emphasised by the author.

There are resonances of the controversies of our own time to be noted in the text. The proposal that two women police officers were to be appointed in Walsall was set aside because there was uncertainty as to whether men would accept the authority of women! In Stoke-on-Trent women were recruited into the work force in the Potteries but were not allowed to carry out heavy work, whereas nearby women were involved in blacksmithing work and were being complimented for their strength in this potentially very strenuous occupation.

This is an extraordinarily interesting book. It is not appropriate to try fully to summarise its contents but rather just to recommend it for its potential to explore the wider reaches of what was happening at a local level on the ‘Home Front’. It has strong value both as a local commentary as well as providing background to the wider national situation, especially given the unexpected source material that has become available within Staffordshire.