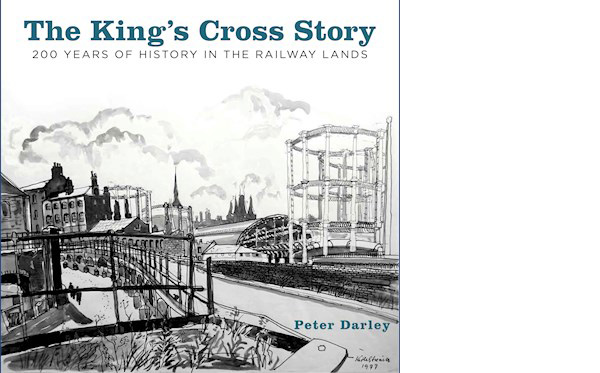

The King’s Cross Story: 200 Years of History in the Railway Lands

Book Review

Peter Darley, The King’s Cross Story. 200 Years of History in the Railway Lands, The History Press, Stroud, 2018, paperback, £20.00, ISBN 978 0 7509 8579 6

Simon Bradley in his foreword to Peter Darley’s ground-breaking exploration of the Great Northern Railway’s celebrated terminus at King’s Cross explains how this book by the Chairman of Camden Railway Heritage Trust promises to ultimately explore the heritage of the railway northwards, ‘taking in tunnels and viaducts, coal drops and canals, warehouses and workshops of every description’ in a holistic study of the railway which from 1846 with its ‘stations, goods depots, locomotive sheds, coal yards and stables at Kings Cross served the needs of an ever-growing metropolis in the second half of the 19th century ‘in the high age of steam’. After the demise of the era of steam, it left ‘a decaying industrial landscape’ on the periphery of the metropolis which eventually ‘was invaded by clubbers, contested by developers and the community and captured by artists and photographers’.

Indeed, Darley’s account of the railway terminus spanning 214 pages, includes some 230 images including original artwork by Katie Strenitz, including an evocative cover image of the industrialised landscape in 1977 which it spawned around its terminus. This had been deliberately carefully ‘limited by statute from approaching closer to the City than the New Road’, thereby keeping at bay, the complementary infrastructure of stables buildings accommodating the ubiquitous working horses which linked the terminus with the metropolitan consumers of milk, grain, flour, fruit and vegetables, fish and cattle, Yorkshire coal and quarried stone and a growing proliferation of other commodities arriving by rail at the metropolis. Collectively the large number of working horses contributed to a multitude of unsavoury odours which also encompassed the consequential atmospheric pollution arising from ‘their posthumous transformation in the hands of knackers and glue boilers’ before the pollution diversified with the arrival of the combustion engine. Goods movements also generated large quantities of paperwork and the necessity of ‘armies of clerical staff’ providing the attendant bureaucracy.

Whilst Darley’s account eschews footnote references, he appends a bibliographical guide to secondary and archival sources which will facilitate further study. His lively study with its maps and other illustrative material will enable both visitors and those ‘who now reside, work, study, dine or play in this new world’ aptly including the authentically retained name of Coal Drops Yard to understand the historical significance of the environment they have inherited.