People and Houses of South-east England c.1300-1900

Review

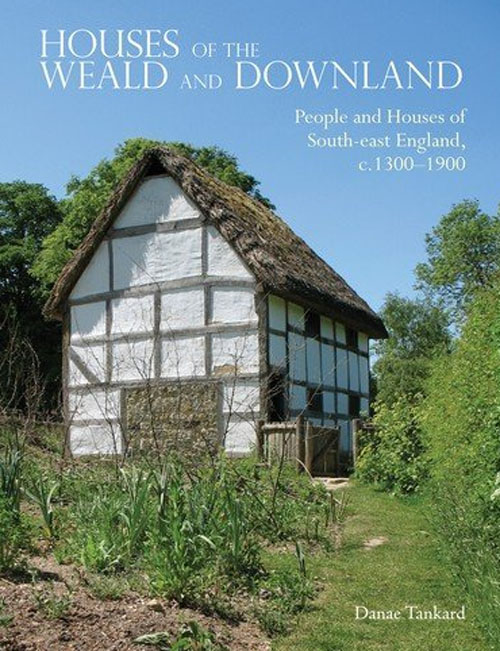

Houses of the Weald and Downland: People and Houses of South-east England c.1300-1900, Danae Tankard, Carnegie Publishing Ltd, 2012, paperback, 214p, 100 illustrations (30 in full colour), ISBN 978-1-859362-0-6, £14.99.

The Weald and Downland Open Air Museum opened in 1970 with the aim of rescuing representative examples of vernacular buildings from the South East of England. Today, the Museum's 50-acre site near Chichester has a collection of fifty traditional buildings illustrating rural living conditions across six centuries. Dr Tankard spent two-and-a-half years as a Knowledge Transfer Partnership associate researching the histories of the most important exhibits in order to answer the question ‘what was life like for the people who lived in these houses?'

This book is the result, and covers eight houses in eight chapters beginning with a 13th-century peasant house and concluding with a pair of timber-framed, mid-Victorian, semi-detached, railway workers' cottages.The features of each building are described with clarity. Key technical terms are explained, avoiding the need for a glossary. Where associated family histories are known they are given and set in context. Consequently a great deal of relevant social and economic history is slotted into the narrative, so that along the way we touch on a variety of diverse topics including nucleated villages; woodland pasture; feudal society and the peasant economy; common land and enclosures; the employment of children; and the migration of a rural working class from the land to towns and to work in industries such as the railway. Much is based on original documents such as probate inventories that afford an insight into how homes were furnished and the multi-functional features (baking, brewing, malting and dairying etc.) of many domestic areas. The time span covered by the buildings allows landmark changes in building techniques (informed by experimental reconstruction undertaken at the Museum) and lifestyles to be explored. An example is the transition from medieval open hall houses (a 14th-century hall house from Boarhunt, Hampshire) via smoke bays (‘Poplar Cottage', c.1630) to houses with chimneys (‘Pendean' an early-17th century farmhouse). ‘Bayleaf', a timber-framed Wealden hall house, the front wall of the hall recessed between jettied end bays in characteristic Wealden fashion (much photographed and the most widely known of the Museum exhibits) reflects this particular change. The oldest parts of Bayleaf date from the early-15th century. Subsequent modifications included the insertion of a brick chimney-stack and a ceiling dividing the open hall into two-storeys by the 1620s.

Notes and references are grouped unobtrusively by chapter at the end of the book, which is beautifully illustrated throughout with a selection of photographs, maps, copies of documents, and extracts from illuminated manuscripts.

The Weald and Downland Museum rescues and restores buildings. Dr Tankard has brought a well-chosen selection vividly to life. But do not make the mistake of thinking this book is simply an expanded guide for Museum visitors. It is much more than that. The buildings studied are skilfully explored as illustrative examples to reveal wide-ranging historical detail. And what this book does singularly well is to provide an evidence-based counter balance to any lingering rosy-hued views of our rural past as a lost golden age of simplicity lived lived in harmonious communities. Anyone with an interest in rural life and buildings will find it an absorbing, informative and thoroughly stimulating read. Highly recommended.