Photographs and Historians: Reflections on some Nazi Era Photos in U.S. Archives

History journal blog

I recently enjoyed what a historian would consider cut-up-the-rug fun; several days of research in the United States National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, MD and the Third Reich Collection in the Library of Congress.

In NARA’s reading room, I lost myself among open shelves containing dozens of photo albums taken by Hitler’s official photographer Heinrich Hoffmann and Eva Braun. At the Library of Congress, I flipped through Leni Riefenstahl’s own photos from making Triumph of Will. When staff brought me an ornate presentation album I had asked for, the bookplate made us all gasp; “Ex Libris Adolf Hitler”. More than any amazing single items, what struck me was the sheer volume; 40,000 images in the LOC’s Third Reich Collection and over 300,000 in the Hoffmann collection.

In a 1982 essay, photo archivist J. Roberts Davison describes the ‘typical historian’s’ approach to photographs. Finally finished writing, the historian rushes to some depository of ‘visual records’, where ‘…he will scan image after image, peering at this one, discarding that one, nodding at another, like a decorator choosing a paint colour or wallpaper pattern’. Finally he will choose something that pleases him, ‘to illustrate my text.’ Examination and selection have taken, at most, a few minutes.’ [1]

Even though this caricature of the ‘typical historian’ pre-dates widespread digitization, the pitfalls it illustrates are still there. Indeed, the risks of misreading context or making superficial judgements have multiplied now that we can find thousands of ‘visual records’ without ever leaving our screens. And it can only get worse with AI generated images…

I’m an art historian. So here are some tips from the discipline that will help sharpen the typical historian’s approach to images as well as generate new ideas for research and writing.

Here is how to begin.

- Be a good historian. Treat photographs like any document. Do not cherry pick or ignore context, like Davison’s caricature. Photos, like documents have levels of meaning. Ask what you ask any written source; who created it, for what purpose and for whom?

- Look at lots of pictures; famous ones, unknown ones, professional and amateur ones. Look at them during—or better yet before—your documentary or library research. This will open new research angles and reveal important insights into what the photographers and audiences in the past found important—or not. It will yield fruitful comparisons. For example, this familiar view of the Nuremberg parade ground, which is pristine in Riefenstahl and Hoffmann’s images, is strewn with litter in an anonymous amateur’s.

- Cast a wide net. Going off topic will yield pictorial information that descriptions of images in catalogs fail to capture. The more images you have seen, the better you will be able to recognize AI generated ones.

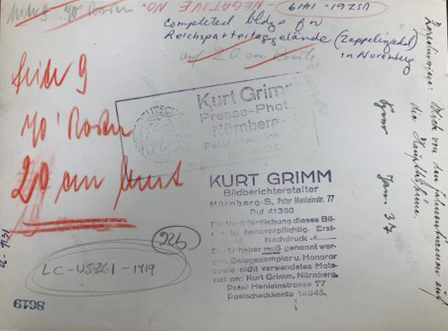

- Like an art historian, seek out originals and multiple versions. Remember what Stalin did. In the LOC, the originals of familiar images of Speer’s models for Nuremberg have handwritten notes and his signature on the back. Hoffman’s contact sheets reveal candid moments as well as before and after moments of well-known images. In our digital era we forget photographs are physical objects with their own stories. A lavish album of photos presented to Hitler tells a different story than a cigarette paper.

- Consider catalog descriptions of an image’s format. Like the difference between an oil painting or a pencil drawing, an image captured on a glass negative from a box camera and one on 35mm film taken on a handheld Leica have different implications. The former takes preparation and forethought, while the latter can be spontaneous and immediate.

- Even with digital images, artistic concepts, such as composition and perspective have meaning. ‘Foreground’ and ‘background’ mean both placement and Close-up or far away, from below or above, the photographer’s position has messages about hierarchy, intimacy or access.

- The best “illustration” may not capture what happened, but mood and metaphor. This unpublished photo of Goering and his pet lion are a better metaphor for the whole Nazi project than yet another portrait of the Reichsmarschall in an operetta uniform. Photographs are choices. Why did the photographer choose that particular subject or view? What did the photographer exclude? Who chose to publish one image rather than another? Why?

- Finally, remember what your own choice of photograph says. Make it a fresh one.

I studied the Leni Riefenstahl and Heinrich Hoffmann collections at the LOC and NARA because of their coverage of the 1934 rally. I was searching for context and clues to the identity of people in a set of glass slides that an uncle brought back as a souvenir from Germany in 1945. The slides, which he had extracted from the wreckage of the Nazi Party headquarters in Wetzlar Germany, appeared to be the personal record of a local party official’s visit to the 1934 Nuremberg Nazi Party Rally.

Madeleine Johnson's book Picnic with Hitler will be published by Chiselbury Press in 2025.

Figure 1: Luitpold Arena, Nuremberg, 1934. Author's Collection.

Figure 2: Zeppelin Field. Library of Congress. Third Reich Collection.

Figure 3: Reverse of Fig. 2 with Speer Office and U.S. Officials' notes. Library of Congress. Third Reich Collection.

References

1. J. Roberts Davison, ‘Turning a Blind Eye: The Historian’s Use of Photographs’, BC Studies, no. 52 Winter 1981-1982, pp. 16-38.